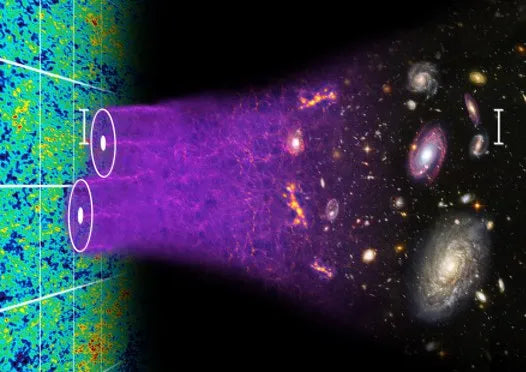

Temperature anisotropies and polarization revealing information about early density fluctuations

A Faint Glow from the Early Universe

Shortly after the Big Bang, the universe was a hot, dense plasma of protons, electrons, and photons interacting constantly. As the universe expanded and cooled, it reached a point (~380,000 years after the Big Bang) where protons and electrons could combine into neutral hydrogen—recombination—thereby drastically reducing photon scattering. From that epoch onward, those photons traveled freely, forming the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Initially discovered by Penzias and Wilson (1965) as an almost uniform ~2.7 K radiation, the CMB is one of the strongest pillars of the Big Bang framework. Over time, increasingly sensitive instruments have uncovered minuscule anisotropies (temperature variations at the level of one part in 105), as well as polarization patterns. These details map tiny density fluctuations in the early universe—seeds that would later grow into galaxies and clusters. Hence, the CMB’s detailed structure encodes a wealth of information about cosmic geometry, dark matter, dark energy, and the physics of the primordial plasma.

2. Formation of the CMB: Recombination and Decoupling

2.1 The Photon-Baryon Fluid

Before ~380,000 years post-Big Bang (redshift z ≈ 1100), matter existed mostly as a plasma of free electrons, protons, and helium nuclei, with high-energy photons scattering off electrons (Thomson scattering). This tight coupling of baryons and photons meant that pressure from photon scattering partially counteracted gravitational compression, generating acoustic waves (baryon acoustic oscillations).

2.2 Recombination and Last Scattering

As the temperature fell to ~3,000 K, electrons combined with protons to form neutral hydrogen—a process called recombination. Suddenly, photons scattered much less frequently and became “decoupled” from matter, traveling freely. This moment is captured in the last scattering surface (LSS). The photons from that epoch we detect now as the CMB, albeit redshifted to microwave frequencies after ~13.8 billion years of cosmic expansion.

2.3 Blackbody Spectrum

The CMB’s nearly perfect blackbody spectrum (measured precisely by COBE/FIRAS in the early 1990s) with temperature T ≈ 2.7255 ± 0.0006 K is a hallmark of the Big Bang origin. The minimal deviations from a pure Planck curve confirm an extremely thermalized early universe with no significant energy injections after decoupling.

3. Temperature Anisotropies: The Map of Primordial Fluctuations

3.1 COBE to WMAP to Planck: Increasing Resolution

- COBE (1989–1993) discovered anisotropies at the ΔT/T ∼ 10-5 level, confirming temperature inhomogeneities.

- WMAP (2001–2009) refined these measurements, mapping anisotropies at ~13 arcminutes resolution and revealing the acoustic peak structure in the angular power spectrum.

- Planck (2009–2013) delivered even higher resolution (~5 arcminutes) and multi-frequency coverage, setting new standards in precision, measuring the CMB anisotropies up to high multipoles (ℓ > 2000) and providing stringent constraints on cosmological parameters.

3.2 Angular Power Spectrum and Acoustic Peaks

The angular power spectrum of temperature fluctuations, Cℓ, is the variance of anisotropies as a function of multipole ℓ, corresponding to angular scales θ ∼ 180° / ℓ. The acoustic peaks appear due to acoustic oscillations in the photon-baryon fluid before decoupling:

- First Peak (ℓ ≈ 220): Tied to the fundamental acoustic mode. Its angular scale reveals the geometry (curvature) of the universe—peak at ℓ ≈ 220 strongly indicates near flatness (Ωtot ≈ 1).

- Subsequent Peaks: Provide information on the baryon content (boosting odd peaks), dark matter density (affecting oscillation phases), and expansion rate.

Planck data capturing multiple peaks up to ℓ ∼ 2500 has become the gold standard for extracting cosmic parameters with percent-level precision.

3.3 Near Scale-Invariance and Spectral Index

Inflation predicts a nearly scale-invariant power spectrum of primordial fluctuations, typically parameterized by the scalar spectral index ns. Observations show ns ≈ 0.965, slightly below 1, consistent with slow-roll inflation. This strongly supports an inflationary origin for these density perturbations.

4. Polarization: E-modes, B-modes, and Reionization

4.1 Thomson Scattering and Linear Polarization

When photons scatter off electrons (especially near recombination), any quadrupole anisotropy in the radiation field at that scattering point induces linear polarization. This polarization can be decomposed into E-mode (gradient-like) and B-mode (curl-like) patterns. E-modes primarily arise from scalar (density) perturbations, while B-modes can come from either gravitational lensing of E-modes or primordial tensor (gravitational wave) modes from inflation.

4.2 E-mode Polarization Measurements

WMAP first detected E-mode polarization, while Planck refined its measurement, improving constraints on reionization optical depth (τ) and thereby on the timeline when the first stars and galaxies reionized the universe. E-modes also correlate with temperature anisotropies, providing more robust parameter fits, reducing degeneracies in matter densities and cosmic geometry.

4.3 B-mode Polarization Hopes

B-modes from lensing are observed (at smaller angular scales), matching theoretical expectations of how large-scale structure lens E-modes. B-modes from primordial gravitational waves (inflation) at large scales remain elusive. Multiple experiments (BICEP2, Keck Array, SPT, POLARBEAR) have placed upper limits on the tensor-to-scalar ratio r. If detected, large-scale B-modes would provide a “smoking gun” for inflationary gravitational waves near the GUT scale. The quest for primordial B-modes continues with upcoming instruments (LiteBIRD, CMB-S4).

5. Cosmological Parameters from the CMB

5.1 The ΛCDM Model

A minimal six-parameter ΛCDM fit typically matches CMB data:

- Physical baryon density: Ωb h²

- Physical cold dark matter density: Ωc h²

- Angular size of sound horizon at decoupling: θ* ≈ 100

- Reionization optical depth: τ

- Scalar perturbation amplitude: As

- Scalar spectral index: ns

Planck data yields Ωb h² ≈ 0.0224, Ωc h² ≈ 0.120, ns ≈ 0.965, and As ≈ 2.1 × 10-9. The combined CMB data strongly favors a flat geometry (Ωtot=1±0.001) and a near scale-invariant power spectrum, consistent with inflation.

5.2 Additional Constraints

- Neutrino mass: CMB lensing partially constrains the sum of neutrino masses. Current upper limit ~0.12–0.2 eV.

- Effective number of neutrino species: Sensitive to radiation content. Observed Neff ≈ 3.0–3.3.

- Dark Energy: At high redshift, the CMB alone sees primarily matter- and radiation-dominated epochs, so direct constraints on dark energy come from combinations with BAO, supernova distances, or lensing growth rates.

6. The Horizon Problem and Flatness Problem

6.1 Horizon Problem

Without an early inflationary epoch, distant regions of the CMB (~180° apart) would not be in causal contact, yet they have almost the same temperature (to 1 part in 100,000). The CMB’s uniformity thus reveals the horizon problem. Inflation’s exponential expansion resolves it by drastically enlarging a once-causally connected region to beyond our current horizon.

6.2 Flatness Problem

Observations from the CMB show that the universe is extremely close to being geometrically flat (Ωtot ≈ 1). In non-inflationary Big Bang, even slight departures from Ω=1 would grow with time, leading the universe to be either quickly curvature-dominated or collapse. Inflation flattens the curvature by huge expansions (e.g., 60 e-folds), pushing Ω→1. The CMB’s measured first acoustic peak near ℓ ≈ 220 strongly confirms this near-flatness.

7. Current Tensions and Open Questions

7.1 The Hubble Constant Tension

While the CMB-based ΛCDM model yields H0 ≈ 67.4 ± 0.5 km/s/Mpc, local distance-ladder measurements find higher values (~73–75). This “Hubble tension” suggests either unrecognized systematics or possibly new physics beyond standard ΛCDM (e.g., early dark energy, extra relativistic species). So far, no consensus resolution has emerged, fueling ongoing debate.

7.2 Anomalies at Large Scales

A few large-scale anomalies in the CMB maps—like the “cold spot,” low quadrupole power, or mild dipole alignment—could be random chance or subtle hints of cosmic topological features or new physics. Planck data see no strong evidence for major anomalies, but this remains an area of interest.

7.3 Missing B-modes from Inflation

Without a detection of large-scale B-modes, we only have upper limits on the amplitude of inflationary gravitational waves, placing constraints on the energy scale of inflation. If the B-mode signature remains elusive at significantly lower thresholds, some high-scale inflation models will be ruled out, possibly pointing to lower scale or alternative inflationary dynamics.

8. Future CMB Missions

8.1 Ground-Based: CMB-S4, Simons Observatory

CMB-S4 is a next-generation ground-based experiment planned in the 2020s/2030s, aiming for robust detection or extremely tight limits on primordial B-modes. The Simons Observatory (Chile) will measure both temperature and polarization at multiple frequencies, reducing foreground confusion.

8.2 Satellite Missions: LiteBIRD

LiteBIRD (JAXA) is a proposed space mission dedicated to measuring large-scale polarization with sensitivity to detect (or limit) the tensor-to-scalar ratio r down to ~10-3. If successful, it would either reveal inflationary gravitational waves or strongly constrain inflation models that predict higher r.

8.3 Cross-Correlations with Other Probes

Joint analyses of CMB lensing, galaxy shear, BAOs, supernovae, and 21 cm intensity mapping will refine cosmic expansion history, measure neutrino mass, test gravity, and possibly uncover new phenomena. The synergy ensures that the CMB remains a foundational dataset, but not alone in exploring fundamental questions about the universe’s composition and evolution.

9. Conclusion

The Cosmic Microwave Background stands as one of nature’s most exquisite “fossil records” of the early universe. Its temperature anisotropies—on the order of tens of microkelvins—encapsulate the imprints of primordial density fluctuations that later grew into galaxies and clusters. Meanwhile, polarization data refine our knowledge of reionization, acoustic peaks, and crucially offer a potential window onto primordial gravitational waves from inflation.

Observations from COBE to WMAP and Planck have steadily improved the resolution and sensitivity, culminating in the modern ΛCDM model with precise parameter determinations. This success also leaves open puzzles—like the Hubble tension or the absence (so far) of B-mode signals from inflation—indicating that deeper insights or new physics might be lurking. Future experiments and synergy with large-scale structure surveys promise further leaps in understanding, whether confirming the inflationary scenario in detail or revealing unexpected twists. Through the CMB’s detailed structure, we glimpse the earliest cosmic epochs, forging a bridge from quantum fluctuations at near-Planck energies to the majestic tapestry of galaxies and clusters we see billions of years later.

References and Further Reading

- Penzias, A. A., & Wilson, R. W. (1965). “A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s.” The Astrophysical Journal, 142, 419–421.

- Smoot, G. F., et al. (1992). “Structure in the COBE differential microwave radiometer first-year maps.” The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 396, L1–L5.

- Bennett, C. L., et al. (2013). “Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Final maps and results.” The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 208, 20.

- Planck Collaboration (2018). “Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters.” Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6.

- Kamionkowski, M., & Kovetz, E. D. (2016). “The Quest for B Modes from Inflationary Gravitational Waves.” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 54, 227–269.